Efforts to the cut greenhouse gas emissions often center on lowering direct emissions from power plants and tailpipes. But there’s a less visible source that, for many companies and institutions, contributes far more to their overall carbon footprint: indirect emissions from their supply chain.

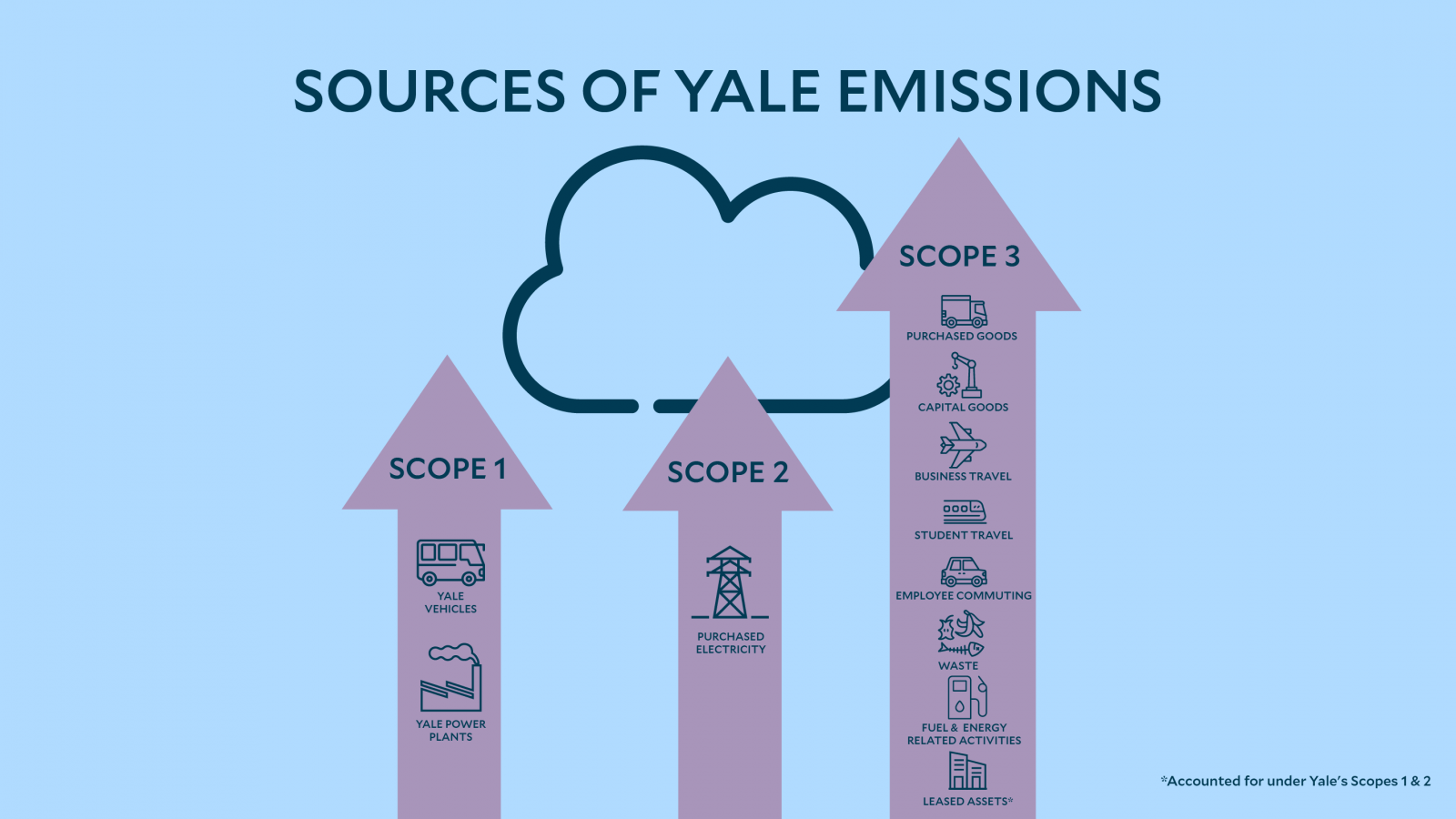

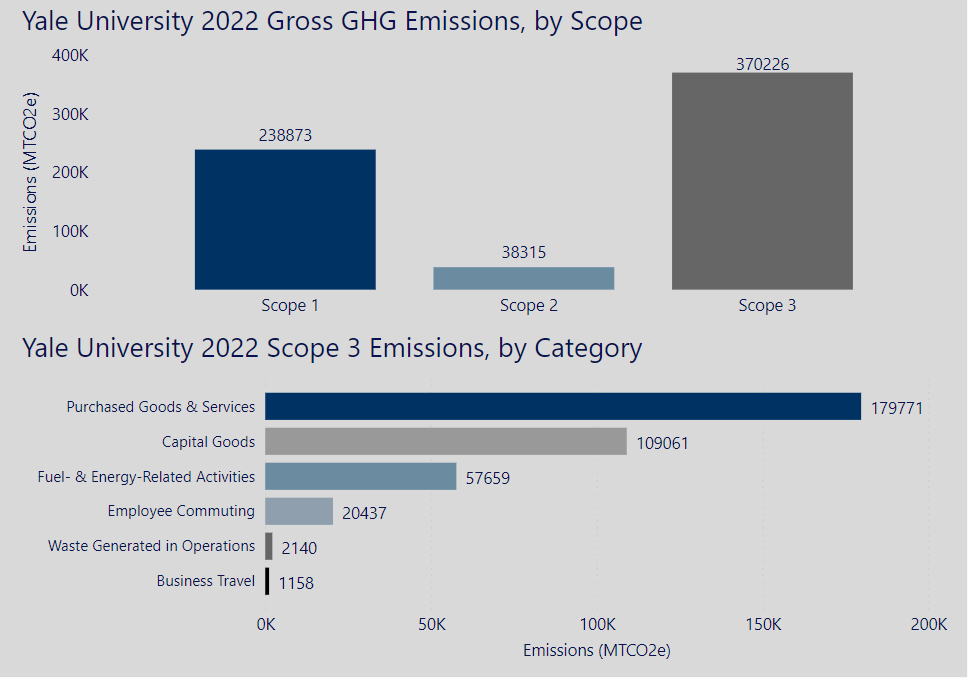

Known as Scope 3 emissions, these are the greenhouse gases generated by the delivery trucks, business travel, employee commuting, and waste generated as part of company operations. To get a complete picture of its environmental impact, an institution must account for all of its emissions—including these indirect sources. At Yale, Scope 3 emissions are estimated to make up 57% of the university’s total footprint in 2022.

Accounting for Scope 3 emissions can be difficult and time-consuming, as there can be literally thousands of sources to catalog and estimate. Reducing them can be even trickier, as the sources of Scope 3 emissions are, by definition, not under an institution’s direct control. But as the climate crisis accelerates, finding ways to curb these indirect sources will be critical to decarbonizing the global economy.

In this Q&A, two Yale experts explain the basics of Scope 3 emissions and the ways that companies and universities—including Yale—are working to understand the impact of their supply chains and lessen their impact.

Lindsay Crum ’15 MEM is Associate Director of the Yale Office of Sustainability and leads the university’s annual accounting of its greenhouse gas inventory, including the complex task of cataloging Scope 3 emissions. Anastasia O’Rourke ’09 PhD is Managing Director of Yale Carbon Containment Lab and a founding board member of the Sustainable Purchasing Leadership Council.

What are Scope 3 emissions?

Lindsay Crum: First, it helps to explain Scope 1 and 2 emissions. Scope 1 are direct emissions from sources owned or controlled by an institution or company—from their power plants and vehicles, and leaking refrigerant gases. Scope 2 are indirect emissions from electricity an institution purchases, for example, from the regional power grid. Scope 3 emissions are also indirect emissions. These occur because of an institution’s activities, but from sources not owned or controlled by them.

Anastasia O’Rourke: It’s important to know that Scope 3 emissions comes from both upstream and downstream emissions. Take, for example, a laptop. What are the Scope 3 emissions associated with it? The upstream emissions would be all the greenhouse gases that went into the production and transportation of the laptop—the machines that extracted the raw materials and assembled it, the trucks that transported the finished product, all the way to it sitting on my desk. The downstream emissions would be when the laptop reaches its end of life, and we take it to be recycled or trashed. First, we’ll have to move it so there’s emissions associated with transport. Then there’s emissions associated with either destroying it or recycling it. There aren’t really any Scope 1 emissions associated with a laptop (its not sitting here emitting now), but there are Scope 2 emissions associated with the power it uses while it’s on and in use. But as you can quickly see, the vast majority of the emissions are in the supply chain outside of my direct control.

Scope 3 emissions are mainly thought of in relation to greenhouse gases and climate change. They do not account for are other environmental or health impacts beyond emissions. In the case of the laptop, we are not measuring the chemicals used to produce it, clean it, or recycle it. There are many other environmental and social impact categories and concerns beyond greenhouse gas emissions, but we don’t tend to call these “Scope 3.”

How are Scope 3 emissions categorized?

Lindsay Crum: Scope 3 emissions are categorized by the World Resources Institute into 15 upstream and downstream categories, which are:

- purchased goods and services

- capital goods

- fuel- and energy-related activities

- upstream and downstream transportation and distribution

- waste generated in operations

- business travel

- commuting

- leased assets

- processing of sold products

- use of sold products

- end of life treatment of sold products

- franchises

- investments.

Why account for Scope 3 emissions in the first place?

Anastasia O’Rourke: Not all products and services have major climate impacts, but we’re trying to get a handle on the full breadth of what our impacts are in order to better manage and reduce them. It’s not just an accounting exercise; we need to know where to prioritize so that we can take action. For Scope 3 especially, I see it as more about decision-making, because we just can’t get very accurate data for each and every good or service that any individual—let alone, organization—is using.

How does a company or university begin to account for its Scope 3 emissions?

Anastasia O’Rourke: Imagine you are a global company buying goods and services in many countries and that you have many different product lines. Thinking about your Scope 3 emissions across all that could be a never-ending task. It could be paralyzing. There’s a suite of tools available that use emissions modeling to generate estimates across those 15 categories. If you’re a company, that helps you determine your largest sources of Scope 3 emissions and where you have potential to reduce them. At that point, you may think about doing primary data gathering from whoever is causing the most emissions. That data gathering is just one step. Ideally you are also then implementing a program to work with your suppliers to reduce those emissions.

Lindsay Crum: The World Resources Institute has developed a protocol that spells out best practices for how to calculate Scope 3 emissions for each category. There’s also the EPA’s Environmentally Extended Input-Output Models, or USEEIO, which Yale uses to calculate emissions of purchased goods and services as well as capital goods.

Anastasia O’Rourke: While these EPA and other models are really helpful, they are still models based on averages. So we can’t use them to say, for example, this garbage that I’m putting in the trash right now is going to have this particular impact. Because depending on what region you’re in, there’s going to be different trash handling, sorting, destruction, waste to energy, maybe a landfill, maybe recycling. You can start to understand why this gets complicated!

What does Yale count as part of its Scope 3 emissions?

Lindsay Crum: Yale was an early adopter for having a greenhouse gas reduction target back in 2005, and we were a relatively early adopter in exploring Scope 3 emissions. Starting in 2008, we collected a subset of Scope 3 data based solely on what we had access to. That was data for: employee commuting, business travel, and paper purchasing. Fast forward to 2017. As part of our goals for the Yale Sustainability Plan 2025, we reviewed all 15 of the Scope 3 categories and asked, what makes sense for Yale to be looking at? And we narrowed it down to five categories:

- purchased goods and services

- capital goods

- waste

- business travel

- employee commuting.

We also added a sixth category that is not currently part of the guidance, and that’s student travel. There’s so much travel happening among our student body—to and from school at the beginning and end of each year, study abroad, and other university-sponsored travel. We explored the possibility of tracking emissions with Yale’s investments, but currently lack sufficient data to do so.

How can a company or university lower its Scope 3 emissions—considering the sources are, by definition, not under its control?

Anastasia O’Rourke: There are some big levers to pull if you are the customer. I’d start with purchasing—understanding which products and services are generating the most emissions and look to purchase lower-carbon alternatives. Or, if your modelling shows that transportation is a big contributor to emissions, you could look to sourcing more locally produced goods, or seasonal products. You can insert climate-related requirements in contracts for purchased goods and services, or at the very least require some reporting on emissions so that suppliers start paying attention. Large purchasing organizations make sure that criteria are not so strict that no one bids on a contract or RFP. It has to be staged over time, ideally with ongoing dialogue and collaboration with suppliers. This kind incremental change can be frustrating to those who want to see fast action. But it’s about understanding how business operates, trying to make change over time to get better results. And again, prioritizing on those categories that are large and where change can be made.

Lindsay Crum: Over the past five years, Yale has worked to refine its process. We measure purchased goods and services—which is Yale’s largest source of Scope 3 emissions—with spending data that are grouped by commodity category. We identified five or 10 suppliers we could reach out to for a conversation about what they are doing more broadly around sustainability, to begin a dialogue about how we can hopefully find areas for reductions. Yale also joined the Sustainability Purchasing Leadership Council, of which Anastasia is a co-founder. That’s been a great way to understand what is happening across sectors—not just in higher ed—and hearing from purchasing counterparts. We also collaborate with peer institutions on purchased goods and services to try to leverage our collective impact as a higher ed sector.

Has the data collected so far yielded any insights about where Yale could achieve Scope 3 emissions reductions?

Lindsay Crum: We have spent the past few years refining our Scope 3 data collection and we are now looking to identify appropriate baseline years against which to measure our progress. As Anastasia noted, it’s also important that when we set goals—whether focused on emissions reductions or other environmental impacts— that they are actionable.

Are public companies mandated to report their Scope 3 emissions?

Anastasia O’Rourke: In the U.S., the answer is no. However, more and more state regulations are requiring reporting and disclosure. California recently said it would like companies in the state to report on Scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions. In addition, the Securities and Exchange Commission is putting out guidance for companies to do more standardized reporting in this area. A lot of investors are very interested in climate risk and climate performance—and how both expose companies to physical risks or business risks. While not regulation, governments can also help by setting up standards for reporting and tools for Scope 3, so it’s less daunting to everyone, as well as by using their own purchasing dollars to improve their own footprint. The U.S. government for example, is the world’s single larger purchaser of goods and services. Change here can really have a ripple effect.

For institutions seeking to reach net-zero emissions, do they account for Scope 3 as part of their net-zero calculations?

Anastasia O’Rourke: Net zero is bit squishy. Most net-zero targets that I’ve seen only account for Scope 1 and 2 emissions. However, there is a movement toward enlarging the net-zero framework to include Scope 3. Where people get hung up is on how to measure it. Who gets to count a reduction—because my Scope 3 will be someone else’s Scope 1 and 2. Do I get to count that against my net-zero? Groups such as the Science-Based Targets Initiative are pushing companies to include Scope 3 in their climate goals. That’s quite an influential group but it’s still a system of recognition and voluntary commitment, and still evolving, too.

Lindsay Crum: Yale’s net-zero and zero actual carbon emissions goals are inclusive of Scopes 1 and 2. We are committed to identifying goals for our relevant Scope 3 categories by 2025.

As Scope 3 accounting evolves, should we expect consumer products to eventually come with labels disclosing the emissions associated with them?

Anastasia O’Rourke: There have been 20 to 30 attempts at this over the years in the U.K. and U.S. It’s quite hard to standardize, as you can imagine. It’s also unclear whether consumers know enough about emissions to make informed choices. I’ve worked on this a lot and the more effective versions are like Energy Star, because people understand when they buy an appliance with that label, the EPA has determined the energy savings are legitimate—and also it’s going to save them money. I do think there is a market there for this kind of information but it’s still pretty niche. From my point of view, you’re going to have a much bigger impact if you work with large institutional buyers than you are with individuals en masse.