Headlines about the state of recycling can paint a fairly grim picture.

Depending where your search engine points, you may learn that of the 40 million tons of plastic waste generated in the U.S. in 2021, less than 6% was recycled. Or that 90% of all plastic shopping bags produced in 2018—some 4.2 million tons worth—were either landfilled or incinerated. Or that the sheer tonnage of e-waste discarded in 2021 outweighed the Great Wall of China, and is on pace to double by 2030.

And yet recycling remains a linchpin of sustainable materials management worldwide—and is crucial to meeting Yale’s sustainability goals. Five days a week, Yale Recycling trucks haul an average of 1.5 tons of recyclable materials to processing facilities so they can be given new life—diverting mountains of material from the waste stream.

Recycling is ubiquitous in our daily lives but it can still seem cloaked in mystery and misunderstanding. In this Q&A, two of Yale’s recycling experts explain how it works at the University—sorting fact from fiction. Jim Reid is Superintendent for Yale Landscape and Grounds and oversees university recycling. Lindsay Crum is Chief Manager for Sustainability Operations & Strategic Data in the Office of Sustainability.

Recycling at Yale is single-stream. We’ve heard this term a lot, but can you explain how it works?

Lindsay Crum: Single-stream recycling means that all recyclable materials (like paper, aluminum cans, and glass and plastic bottles) go in one bin rather than being separated at the point of disposal. Once recycling reaches its final destination at the material recovery facility, or MRF, the separation takes place. The goal of single-stream is to make it easier for the user.

Jim Reid: We also have cardboard that goes into separate containers and compactors. So what you’ll see in the single-stream containers is just one portion of the overall recycling that we have at Yale.

What’s the easiest way to figure out what is and isn’t recyclable at Yale?

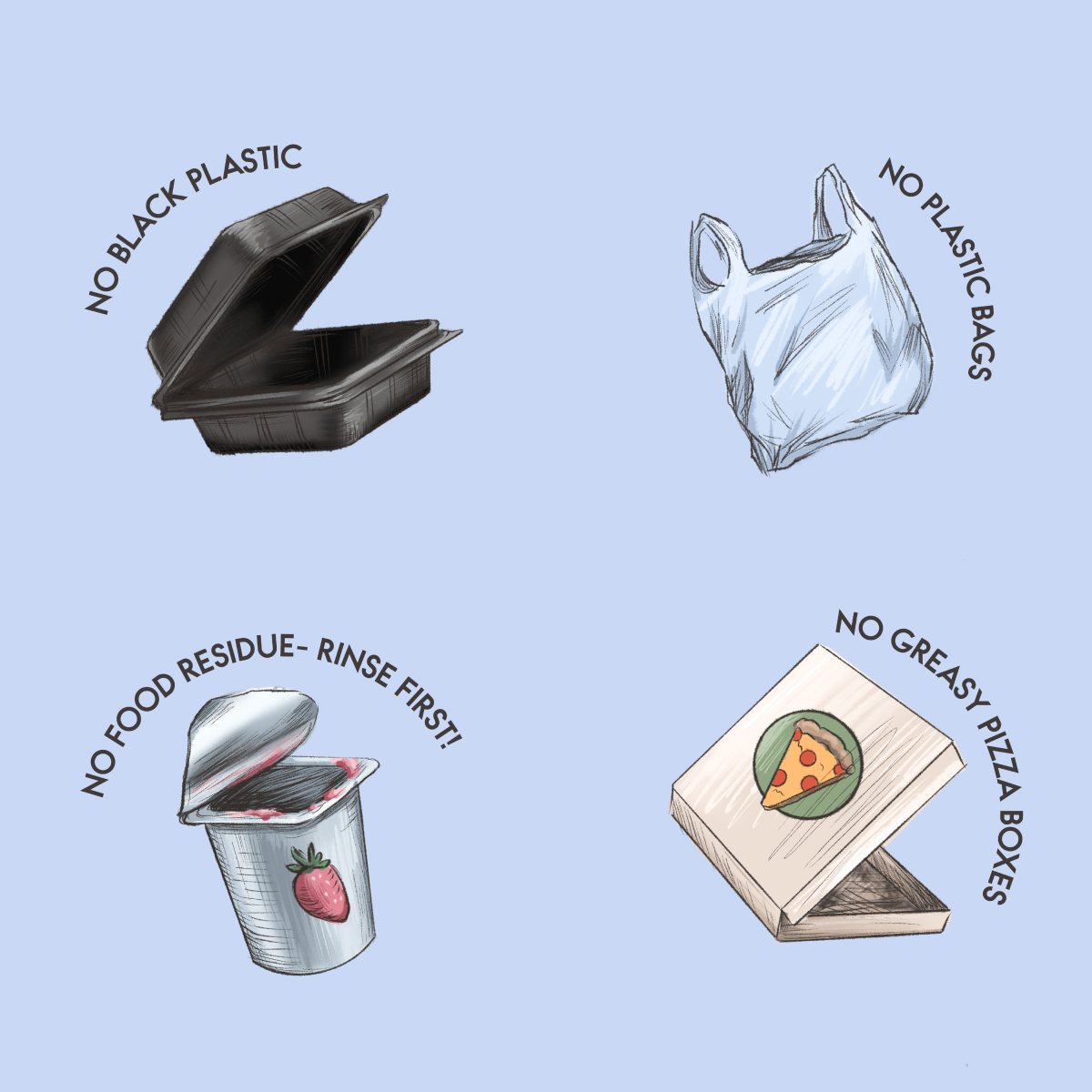

Lindsay Crum: In addition to referring to the university signage, the RecycleCT Wizard is a great tool to search for specific items. Glass bottles, aluminum cans, paper—all of that can be recycled single-stream if they are empty and clean. Some common items that cannot be recycled are plastic bags (although these can be collected at your local grocery store), black plastic (due to inability for the MRF technology to “see” or recognize it as plastic), pizza boxes with residual grease or cheese on them, or anything contaminated with food residue. Two good rules of thumb are:

- Anything smaller than a credit card won’t get recycled because it will slip through the sorting machines at the material recovery facility.

- You should not put anything into single-stream recycling that is made of more than one kind of material. For example, something with both plastic and metal parts should not go into single-stream recycling. The machines at the material recovery facility won’t be able to tell what it is, and therefore won’t know how to sort it, and it will get discarded. If you can easily take the different material types apart—and if they are big enough—they can be recycled. This is why design for disassembly, where an item can be easily separated into component parts, is such an important concept, and why it’s exciting to see certain companies developing their products in this way.

Illustrations by Emily Cai ’25

What about campus e-waste?

Lindsay Crum: Laptops, printers, keyboards and other e-waste can be disposed of through Yale Environmental Health and Safety.

There’s a sentiment that comes through in sustainability surveys issued to the Yale community—and that permeates the wider culture—which is a sense that a lot of recycling doesn’t actually get recycled, but rather gets combined with trash and therefore ends up in the landfill. Can you clarify this?

Lindsay Crum: I think there are a few things happening here. There are instances where recycling does go into the garbage because it’s too contaminated with trash or food waste. That’s why it’s so important that we reduce contamination and address what is appropriate to recycle and what isn’t. The operating landfills in Connecticut are not processing municipal solid waste—the ones currently active only accept bulk waste and larger items. So recycling is not going to a landfill. As for our trash, that’s going to a waste-to-energy facility called the Wheelabrator, in Bridgeport.

Jim Reid: Yale does an excellent job with recycling: we have the right program, use the right haulers, get it to the right facilities. If you get your piece into the recycling can, there’s a very good chance it’s going to get where it needs to go. The only stumbling block is contamination.

What are the biggest sources of contamination?

Jim Reid: Plastic bags—primarily the blue can liners we use at the point of collection—are probably the number one offender at material recovery facilities for two reasons. Empty bags clog up the sorting machines. A full bag of recycling that’s put on the sorting machine will end up as trash because the machine can’t recognize what kind of material it is. The workers there can’t open every bag, take out the recyclables and sort them. That’s just not a practical thing to do. So anything that gets to these facilities in plastic bags goes out as trash. We’re working very closely with staff at Yale to make sure that they empty those plastic bags and don’t mix them in with recycling. Some contamination also happens at the user level—usually at bigger events because there’s a lot of moving parts and people aren’t always paying attention to what goes into the recycling bin.

How contaminated is too contaminated? At what point does an individual piece of recycling – or a batch of recycling – become so contaminated that it’s thrown out?

Jim Reid: If a recycling bin has 80 percent recycling with 20 percent trash mixed in, we could put that on our truck because most of it is recyclable. There are times where certain foods or trash are put in a recycling bin and it gets all over everything. In that case, it all goes to trash.

Lindsay Crum: For individual items, a quick rinse is usually sufficient. If food residue on a container is easily visible and widespread, either clean it or don’t recycle it. Also, be sure to empty out any liquids.

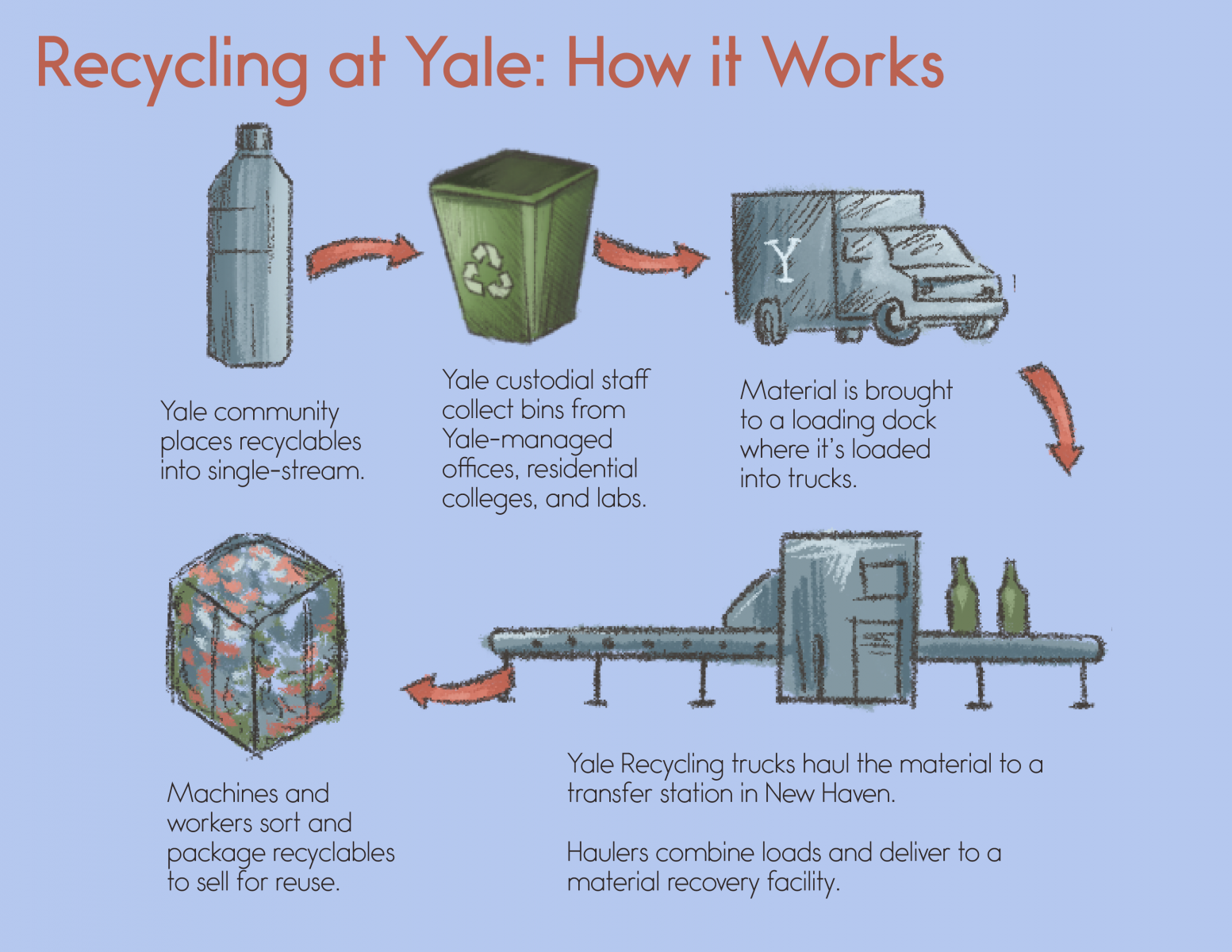

Where does Yale’s recycling actually go? How does it get from the deskside can to the material recovery facility?

Jim Reid: Starting at the deskside can, custodial or grounds staff collect from the individual recycling containers and bring material to one of Yale’s docks or trash collection areas, where it is placed into the proper containers. Then Yale Recycling comes with our own drivers and trucks and the material is taken to one of two transfer facilities here in New Haven. There it’s combined with loads from other haulers and brought to a material recovery facility where it is sorted by material type. This takes place five days a week at Yale. We have three main recycling trucks that transport an average of 1.5 tons of recyclable material every day.

Lindsay Crum: Once everything gets sorted, the material gets baled together and now it’s a commodity. The glass gets pulverized, the paper gets baled together, the plastic gets flattened and baled, and those materials then get sold per ton. And clean material fetches a higher price than contaminated material.

How many employees does it take to manage recycling at Yale?

Jim Reid: We have four drivers, but we have hundreds of custodians and dozens of groundskeepers, as well as dozens of dining staff and thousands of other employees all making this happen.

The thinking about recycling has evolved a lot in the past five to 10 years due to consumer habits and global economics. How important is recycling nowadays to the overall goal of waste diversion? Is it still worth it?

Lindsay Crum: I think the answer is yes, it’s absolutely worth it provided we address this contamination issue. That’s the key to making this worthwhile. When the materials are clean and sorted properly, it’s a really great system and it works. As long as consumers are buying recycled items, the demand is there. When we talk about our day-to-day materials management, diverted materials are the things that don’t go to municipal solid waste or garbage. So diverted material for us is single-stream recycling, organic food waste and reuse items collected through programs like Spring Salvage. Recycling is the largest piece of that pie at Yale.

There are a lot of discouraging headlines about recycling—namely that recycling plastic is becoming difficult, if not impossible, in part because of China’s policies. How is that impacting Yale or Connecticut?

Lindsay Crum: A lot of the headlines have to do with China no longer wanting to accept recycled material from the United States. That’s true. Several policies have been put in place by China about how much contamination they are willing to accept in recycled material they purchase. Connecticut and therefore Yale—our recyclables were not going to China. The way our markets were working, it was staying domestic. So the China policy didn’t directly impact us; it had an indirect impact on us because other parts of the country had been shipping out to China and then needed to change course, so we were deemed competition internally in the United States. One positive result of this “competition” is that domestic facilities are upping their game and ensuring more streamlined practices. They are also wanting clean materials, which underscores yet again the need to limit contamination.

What behaviors can we as individuals adopt to help solve this problem—or to reduce the need to recycle in the first place?

Lindsay Crum: Don’t use so much stuff to begin with, and if you are using something make sure you can use it more than once. And that can be tricky, right? Because you’ve got that classic example of the reusable tote bag. Everybody is giving away tote bags but if you don’t keep using it, it’s actually worse than a paper bag in terms of the energy and resources it took to create the plastic tote bag.

Jim Reid: At some point during the year, every department at Yale should take a minute and assess how they are impacting the university through a sustainability lens. If everyone did just a very small, thought-out reduction—wow, it could be huge.

Do Yale purchasing standards say anything about buying post-consumer materials?

Lindsay Crum: Yes. Yale has established sustainable purchasing standards for everything from copy paper and toner cartridges to light bulbs, appliances, and office furniture. It sounds so simple, but also just have an awareness of what you already have before you purchase, for instance, office supplies. That’s a very small-scale example but multiplied across the University it could have a big impact.

Jim Reid: I think purchasing could have the biggest future impact on our recycling efforts. There are trucks downtown every day bringing in so many materials to Yale.

What are your main recycling priorities for 2023?

Jim Reid: Number one is contamination, for example ensuring that blue bags and liquids stay out of the recycling. If we could fix all the internal contamination issues from all of our campus users, I am telling you the rest of the system is very solid. This has been going on for a long time at Yale. This is not a new thing. If we can eliminate internal contamination, it’s nothing but up from here.

For more resources on recycling at Yale, visit our Managing Materials page.