January 21, 2021

Forestry expert Terry Baker and environmental health expert Dr. Kai Chen walk us through the causes, effects, and future of wildfires in North America.

What causes wildfires?

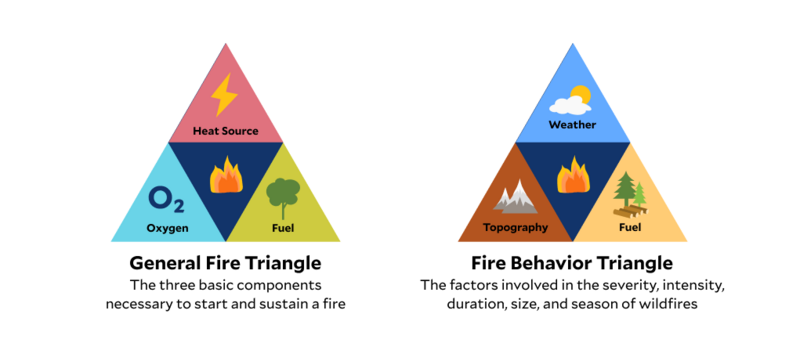

“When it comes to the causes of wildfires, there are two triangles to understand,” Terry Baker (’07 MF), CEO of the Society of American Foresters, says. “The first is called the ‘General Fire Triangle’. Its three sides are the three components you need to start a fire, including a heat source, oxygen, and fuel. The second is the ‘Fire Behavior Triangle’, which includes fuel, topography, and weather.”

Baker explains that fuel is a critical component to any fire. In a wildlife setting, fuel is anything that can burn – like various types of vegetation.

“It’s the accumulation of fuel over time that really creates the space to have some of the large impactful fires that we’ve seen over the past few years,” Baker adds. He points out that while some wildfires are ignited by heat sources such as lightning, up to ninety percent of wildfires are started by humans. While there are cases of arson, many wildfires are started accidentally; for example, from campfires left unattended, cars that backfire, or lawnmowers that spark.

Are wildfires getting worse and/or occurring more frequently?

Our experts agree that wildfires and their seasons are becoming longer and more intense. Baker explains that human activity played a big role. “If ninety percent of fires are started by human beings, and our population is growing, and people are expanding out into more rural areas or going and recreating in natural areas more often, it’s just a matter of time before statistically you’re going to start seeing more and more fires start,” Baker says.

Some of the responsibility also rests on practices by fire and forest management professionals as well as federal, state, and local government policies. Indigenous techniques around forest management and wildfire prevention involves clearing out this growth with controlled fires and cultivating the cleared land, which helps to prevent uncontrollable wildfires. However, in many cases, this knowledge has been ignored, legally prohibited, or lost all together.

“A lot of this increase in wildfires has to do with forest management practices, or lack thereof,” Baker says. “Historically, firefighting standards focused on putting fires out as quickly as possible and keeping the fires as small as possible. That’s a great idea from a safety standpoint. Recently, there have been more efforts to manage wildfires for resource benefit including the reduction of vegetation density. Past firefighting practices, challenges to active forest management, and fears of prescribed fire have allowed forests to grow unchecked. Under increasingly frequent weather conditions, those forest conditions are highly susceptible to fire starts that quickly become difficult to control.”

However, even beyond the ignition and management of wildfires, humans are also causing more dramatic changes to wildfire seasons. “A key reason we are seeing more frequent, more intense wildfires has a large extent to do with climate change,” says Dr. Kai Chen, PhD, Assistant Professor of Epidemiology at the Yale School of Public Health and Director of Research at the Yale Center on Climate Change and Health. “Climate change is literally fueling the wildfires by changing the weather parameters included in the components of a wildfire.”

Chen calls rising temperatures, decreasing rainfall and increasing drought patterns – all of which are effects of climate change – particularly concerning.

“A hotter season paired with drier vegetation can lead to more wildfires that are harder to contain,” Chen says. “Stronger winds also add more oxygen to fires, allowing them to spread even faster.”

Due to climate change, wildfires and their impacts are expected to increase dramatically. “Climate change models project that if we follow the current pathway of greenhouse gas emissions, which is called a ‘business as usual’ pathway, then there will be more frequent and more intense wildfires through the end of the century,” Chen says. “Because of this, the majority of the world’s population will experience a greater risk of wildfire exposure.”

What are environmental and human health impacts of wildfires?

Wildfires have significant impact to the environment, including the vegetation, wildlife, and people who live in their path. Our experts explain that intense fires can cause significant damage to soil as well as the complete removal of vegetation. Such destruction can lead to flooding and landslides that destroy habitats and property while degrading the local water quality. Forest critters may also be displaced, or worse.

“While some species have developed instincts over thousands of years to sense fires and get themselves to safety, depending on the conditions and fire behavior some of these larger fires cause more of an impact to wildlife,” Baker says.

Wildfires cause serious direct and indirect impacts to human health. People living directly in the path of wildfires can sustain serious burns and injuries, and many have died. Further, Chen points out that the firefighters managing the wildfires are also vulnerable to heat exposure. He cites many studies of firefighters who experienced serious dehydration, heat stroke, and mental distress from fighting wildfires.

Even those who manage to evacuate can experience the loss of their homes, property, and natural resources, causing financial and mental distress. “These extreme events leave them with serious trauma,” Chen says. “Depression and post-traumatic stress disorder are also a direct impact of wildfires.”

Neighboring communities that are not directly in the path of wildfires can also be affected by significant air pollution. Chen explains that wildfires generate toxic gases and particulate matter that can get trapped in your cardiovascular and respiratory systems, causing devastating impacts on your morbidity and mortality. However, there are many knowledge gaps in understanding the overall impact of wildfires on public health, including long-term health impacts and impacts on a full range of health endpoints such as adverse birth outcomes.

What environmental justice concerns arise due to wildfires?

The impacts of wildfires do not affect everyone equally. “Low-income communities and communities of color have disproportionate exposure to the effects of wildfires,” Chen says, explaining that individuals from these communities are less likely to be able to evacuate or work from home during an emergency. “Maybe if you have a second home, it’s easy to evacuate. But if you’re a low-income individual, you don’t have the luxury to just abandon your home.”

Baker adds that vulnerable populations are less likely to have financial resources to protect themselves with high quality masks and air filters and to manage their pre-existing conditions. This heightens their exposure to and impacts from air pollution. They are also less likely to afford mental health resources to help cope with the experience.

The damage done to the infrastructure of vulnerable communities is also disproportionate. “Compared to wealthier homes that sit on an acre of land, low-income communities often have densely populated homes and are more susceptible to wildfires,” Baker explains. “This is simply because it is easier for a wildfire to spread from one residence to the next.” These communities, our experts point out, are also less likely to have homeowner’s insurance; wildfires, in these cases, create an insurmountable financial loss.

What can we do prevent wildfires?

To prevent wildfires, Baker explains, forestry professionals work to manage the fuel – trees, vegetation – available to fires. To do so, they will often use a technique called prescribed burns, which involves intentionally setting small, controlled fires to reduce the impacts of a larger wildfire. Some states like California are successfully returning to indigenous fire management practices, which involves intentionally setting fires to not only reduce the risk of wildfires, but also to make room for new, nutrient-rich growth and more sustainable habitats for animals and humans.

Baker suggests acquiring an understanding and acceptance of the sustainable forest management practices of your local forestry professionals, even if it means that certain trees are purposely cut or burned. Using the best available science and years of on-the-ground knowledge, forestry professionals can implement an array of sustainable forest management activities that help to improve the health and resilience of landscapes. Common practices can include thinning overcrowded forests for better wildlife habitat and forest health or removing or containing harmful invasive plants. Citizens also have the ability to help prevent wildfires; Baker also encourages individuals to become educated about the human causes of wildfires and heeding the advice of forestry professionals.

“Be mindful of your behavior,” Baker suggests. “If you’re living or recreating in or directly adjacent to forested landscapes, you need to be conscious of the weather and aware of the risks that your activities pose. If you hear the term “Red Flag” from your local foresters and weather professionals, know that it isn’t a great time to go barbecue or even mow the lawn.”

Wildfires will continue to happen, so while it is important to obtain a working knowledge of your community’s emergency plan for handling the incident, Chen explains that it is also essential to get to know your community’s climate action plan.

“We can all contribute to mitigation of wildfires by fighting climate change,” Chen says. “We need to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions to limit global temperature rise. Some studies show that if we meet the goals of the Paris Climate Agreement, we can avoid a significant increase in wildfires. It relies on large governments, corporations and industries to lead this effort, but we as individuals also have the responsibility to reduce our emissions to protect others.”

What is Yale Doing?

Yale Center on Climate Change and Health (CCCH) is conducting research to fill the knowledge gaps about the health impacts of wildfires under a changing climate. Michelle L. Bell, Mary E. Pinchot Professor of Environmental Health and a member of the Advisory Board of CCCH, has led several projects to understand and project the health risks of wildfire smoke exposure in the Western U.S. and elsewhere under climate change. CCCH utilizes Yale’s multidisciplinary expertise and global reach to train future leaders, provide a comprehensive educational program, and catalyze innovative research, all to address one of the greatest public health challenges of the 21st century.