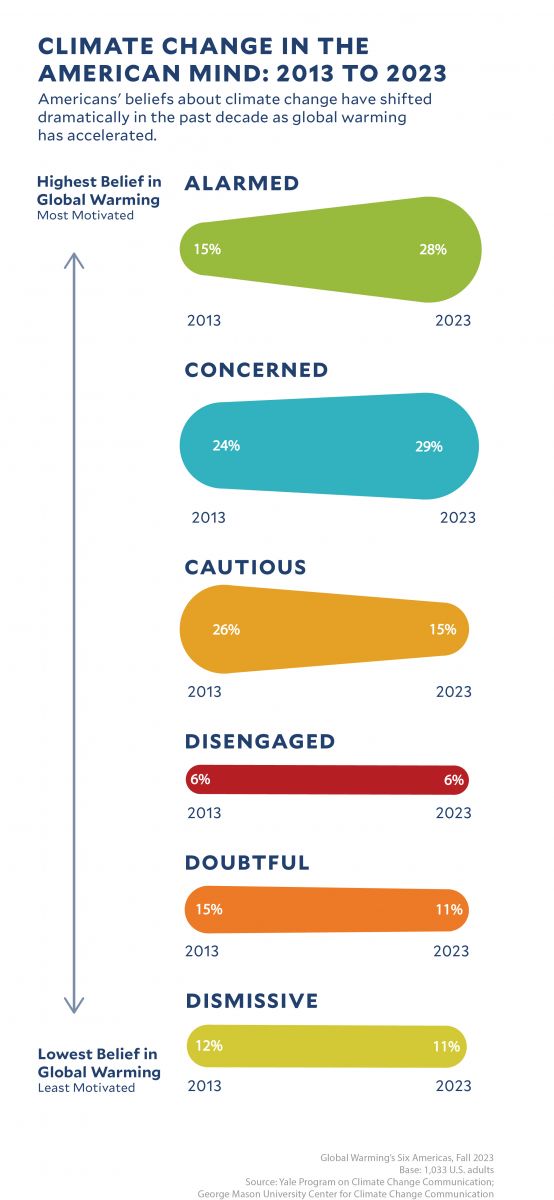

American voters’ attitudes about climate change have shifted dramatically over the past decade. A majority of Americans are alarmed or concerned about the state of the planet and more than two-thirds support a variety of government policies to address it.

And yet climate change has been largely absent from the 2024 presidential campaign, overshadowed by concerns over immigration, the economy, and democracy itself. In the September presidential debate, global warming wasn’t asked about until the final question, leading one science historian to declare that “climate is really not on the ballot this fall.”

The Yale Program on Climate Change Communication (YPCCC) has been tracking changes in American beliefs and attitudes toward global warming for nearly two decades and developed the groundbreaking “Six Americas” framework for understanding the range of viewpoints about climate change. As the 2024 election enters the homestretch, YPCCC Director Anthony Leiserowitz discusses the politics of climate change, what’s at stake in this election, and why climate groups aren’t as politically powerful as they could be. This interview was condensed and edited for clarity.

The narrative around climate change often gets reduced to the idea that there are climate deniers and climate alarmists–with nothing in between. What is the reality?

Americans don’t have a single viewpoint about climate change or, frankly, any important issue. Too often people simply divide the public into climate change believers vs. deniers. But that is way too simplistic and not a very useful framework for strategic communication. Seventeen years ago, we at the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication and our partners at George Mason University conducted what’s called a segmentation analysis and identified Global Warming’s Six Americas—six distinct audiences within the United States that each respond to global warming in a different way.

What are the six Americas?

The first group we call ‘the Alarmed’—that’s 28% of the country. They are firmly convinced global warming is happening, it’s human caused, they’re very worried about it, and they strongly support action.

The second group is ‘the Concerned’—29% of the country. They think it’s happening, human-caused, and serious, but they still tend to think of the impacts as distant in time and space.

Then comes a group we call ‘the Cautious’—the 15% who are still on the fence. They wonder if it’s real, if it’s human-caused, and if it’s serious.

‘The Disengaged’ are 6% of the population. These are people who say they’ve never heard of global warming and don’t know what the causes or consequences are. There’s not usually an ideological barrier, they just don’t know anything about it.

‘The Doubtful’ are the 11% who think global warming probably isn’t real, but if it is, it’s just a natural cycle—so there’s nothing we as humans can do about it.

Last but not least are ‘the Dismissive’—those who are firmly convinced it’s not real, it’s not human-caused, it’s not a serious problem, and are often conspiracy theorists. They are only 11% of Americans, but they’re really vocal and they’re more than adequately represented in the halls of Congress; others have estimated that about 23% of Congress fall into this category. They tend to dominate the public square because they are so loud.

What effect are ‘the Dismissive’ having on the politics of climate change?

They have created a social condition where many people are afraid to talk about climate change. It’s what we call the spiral of climate silence. Let’s say I’m someone who would like to talk about climate change, but I don’t know what’s inside your head. And if my perception is that half or more of the country is Dismissive, I may be reluctant to bring up a subject that might start a fight. And most people don’t want to start an argument about something that they’re not that confident about in the first place. And so climate change has joined sex, religion, and politics as topics that some people are afraid to talk about at the Thanksgiving Day table.

How have Americans’ attitudes on global warming changed over the past 10 years?

We’ve seen profound changes. Back in 2013, the Alarmed were about 15% of the population and the Dismissive were 12%; the two groups that are most passionate about this issue were essentially tied. Fast forward to just a few months ago, and now the Alarmed have grown by 13 percentage points to 28%, while the Concerned have also grown to 29% of the country. By contrast, the Dismissive haven’t changed much—they’re at 11%. That shift helps us understand why we’ve seen such progress on taking climate action. Let me quickly say: not enough, not fast enough. We’ve got plenty of work left to do. But nonetheless, the United States at the federal level has passed by far the biggest climate bill in its history and, arguably in the history of the world. You’ve seen states and cities pass important climate legislation, companies taking action, and citizens getting more engaged. That’s all part of this deeper shift in the underlying social, cultural, and political climate of climate change.

How much do people know about the Biden administration’s landmark climate law, the Inflation Reduction Act, and what are their opinions of it?

Less than half of Americans have even heard of the inflation Reduction Act and that includes liberal Democrats. But when you give them a description of what’s in the act, most Americans support it—around 70%. But there are a lot of issues at stake in this election and that makes it harder for the climate message to cut through.

What is at stake in this election in terms of climate policy and global warming?

Many vital climate policies—including the transition to clean energy, investments in underserved and more vulnerable communities, and participation in international climate treaties—will be determined by voters’ choices in the 2024 elections.

Do Americans support action on climate change?

The Six Americas model is very predictive of people’s desire for action. ‘The Alarmed’ strongly support all kinds of government responses. ‘The Concerned’ also support action, just not as strongly—and so on. It’s pretty much a stair step all the way down with the exception of ‘the Disengaged’ because they just don’t know much about climate change. In political terms, you might call them low-information voters.

When you start looking at individual behaviors, people sometimes take pro-climate actions but not necessarily for climate reasons. For example, putting solar panels on your roof is not always driven by concerns about climate change. A few studies have shown that Republicans are slightly more likely to have put solar panels on their roof than Democrats. Often that’s about being self-reliant, protecting themselves in case the grid goes out, or saving money. From a climate system standpoint, it doesn’t matter whether you’re installing solar because you care about polar bears or your kid’s asthma or to save some money – what ultimately matters is reducing carbon pollution from coal, oil, and gas.

Are people’s attitudes about climate change translating into how they vote?

Yes, absolutely. For the past few election cycles, we’ve started asking Americans how important climate change is to their vote compared to other issues such as the economy, inflation, education, the war in Ukraine, etc. Among all registered voters, climate change is 19th out of 28 issues this year. But when you break it down by political party and ideology, you see that among liberal Democrats—the base of the Democratic Party—climate change is number four. It’s been as high as number two in recent years. That’s unprecedented in American history and goes a long way to helping us understand why some progress has happened.

How have Democrats responded to that shift in their voters’ priorities?

Back in 2020, when it was an open Democratic presidential primary, the candidates were all competing with one another over who had a stronger climate plan. You had two candidates, Jay Inslee and Tom Steyer, who mostly centered their campaigns on climate change. Many Democratic voters were really passionate about this issue and running on climate change became a strategy. What’s also really interesting is that in 2020, Joe Biden’s climate platform actually got stronger in the general election. Why is that? Increasingly elections are won not merely by persuading undecided voters, but by getting your own voters to actually show up and vote. And two critical demographics that care about climate change in the Democratic coalition were young people and people of color who historically do not vote at the same rate as the rest of the country. This year, there’s an opportunity for Harris and Walz to ride the issue of climate change into the White House. It’s clearly not the only issue that’s important to people, but it’s an important one for many of those key demographics they need to motivate to vote, such as young people.

How influential are climate groups in U.S. politics today?

I don’t think the climate community, writ large, is particularly well organized for power. Most climate groups tend to focus on policy—they make rational arguments for why and how we ought to reduce carbon pollution. Of course that’s critically important, but it’s weak if you can’t deliver votes or flex political muscle. Unions are well organized for power. The National Rifle Association is very well organized for power. The NRA is about 4 million members in a population of over 300 million but they punch way above their weight because they are organized for power. The climate movement is potentially much larger than this but they’re not as organized. We asked the Alarmed if they’d be willing to join a campaign to convince elected officials to take action and an estimated 37 million of them say they would. But they’re not organized.

Your surveys have showed that majorities of Americans believe climate change will harm animal species, the world’s poor, and other people in the U.S. But only 44% believe it will harm them personally. What explains that disconnect?

This is a pattern that I first identified 25 years ago and it still exists today. Many people still perceive that climate impacts are far away in time or that it’s about polar bears or perhaps developing countries—but not the US, not their communities, not themselves. In part, that’s just the nature of living as a human being on this planet—we all have an incredibly narrow slice of reality that we have direct access to. Humans can overcome the tendency to be self or locally focused but it can be harder in the United States where we tend to celebrate rugged individualism. And it’s difficult to think of an issue that’s more of a collective action problem than climate change.

What can voters who are concerned about climate change do in this election?

The most important thing you can do is vote. Your vote matters even if you don’t live in a swing state because we aren’t just voting for president, we are voting for senators, members of Congress, city mayors, governors, state legislators and so on. Secondly, you can join a group working on climate change, which is much more effective and fun than trying to take on climate change all by yourself. You can dramatically increase your power and impact by joining with others. When it comes to political organizing, one plus one doesn’t equal two—one plus one equals 10.

What is Yale doing?

The Yale Program on Climate Change Communication conducts scientific studies on public opinion and behavior, educates the public about climate change, and helps build public and political will for climate action. The Center recently published Resources on Climate in the 2024 U.S. General Election, a round-up of election-relevant resources and insights. Learn more about YPCCC at their website