Ocean health experts Dr. Ellen Thomas and Dr. Catherine V. Davis walk us through a consequence of climate change impacting marine ecosystems and human livelihoods.

What is ocean acidification?

“Ocean acidification refers to the whole suite of chemical changes that happen in the ocean when you start decreasing pH in ocean waters,” says Dr. Catherine V. Davis, Yale Institute for Biospheric Studies Gaylord Donnelley Postdoctoral Associate in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences.

Davis explains that as you add carbon dioxide to a liquid, it will decrease the pH and start to form acids.

“Think about the difference between carbonated water and tap water,” Davis says. “The carbonated water has carbon dioxide in it and forms acid, which gives you that tingling sensation on your tongue. A similar thing is happening in the ocean, with obviously some larger scale changes associated.”

Dr. Ellen Thomas, Senior Research Scientist in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, further explains that the ocean is not turning into acid, per say. Instead, it is just becoming less basic.

“Remember the pH scale from elementary school,” Thomas says. “There is a number seven in the middle. Everything lower than 7 is acid, and everything higher than 7 up to 14 is basic. Before human activity, the ocean was 8.2 on that logarithmic scale, and we have now moved down by one pH unit to 8.1. The ocean is still basic, as it is still to the right of that value seven, but it has moved towards this direction of more acid – which is very serious.”

What causes ocean acidification?

“As with global warming, the science around the causes of ocean acidification is clear, decided, and has been known for over one hundred years,” Thomas says.

Our experts explain that ocean acidification is happening as a direct consequence of the amount of carbon dioxide we are emitting into our atmosphere through human activities, like the burning of fossil fuel. Oceans are carbon sinks, meaning that they naturally absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere through physico-chemical and biological mechanisms.

“The more carbon dioxide you put into the atmosphere, the more will be taken up by the ocean,” Davis says, adding that scientists currently believe that about 25% of all carbon emissions are being absorbed by the ocean, making it one of the world’s largest carbon sinks.

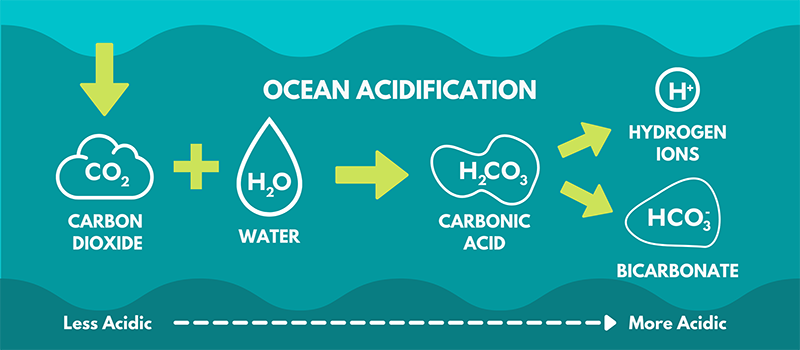

The science behind the absorption is simple. Atmospheric carbon dioxide is first transferred into the surface seawater, where it dissolves and enters into a series of chemical reactions. The carbon dioxide (CO2) reacts with water molecules (H20) to form carbonic acid (H2CO3). This compound breaks down into a hydrogen ion (H+) and bicarbonate (HCO3-).

“The concentration of hydrogen ions in the water determines the pH of the ocean, and adding more hydrogen ions to the ocean water makes it less basic and more acidic,” Thomas says.

How do we know ocean acidification is happening?

Oceanographers have been observing and measuring ocean acidification over the course of the past century.

“When we talk about measuring ocean acidification, we mean either directly measuring the total amount of carbon dioxide in water, the pH of water, or a combination of those precise measurements,” Davis says.

One technique to obtain extremely precise ocean acidification measurements involves collecting water samples directly from the ocean at marine stations, and then taking the samples to analyze in a lab. Another technique designed for taking rapid measurements of ocean acidification involves setting instruments out in ocean water to capture ocean acidification over time and at a variety of ocean layers, from surface to deeper. Observations can be transferred from floats or marine-mammals to satellites.

Thomas points out that the measurements of carbon dioxide in the ocean as well as ocean pH are often studied by scientists in the context of increasing carbon emissions. When the data are overlain, it is clear that increasing carbon emissions across time are directly correlated with increasing carbon dioxide and decreasing pH in ocean waters.

“Even beyond scientific measurements, the effects of ocean acidification are becoming more apparent and more measurable, particularly for coastal communities,” Thomas adds.

What are the impacts of ocean acidification on marine life?

There are two main impacts of ocean acidification on marine life.

“We know that some of the most vulnerable organisms are those that build shells or skeletons out of carbonate minerals, which are directly impacted by acidity,” Davis says. “For animals that rely on carbonates, their shells could be susceptible to dissolution. Before that extreme case happens, it will take these organisms more energy to build their skeletons or shells.”

Thomas explains that this is the case because while shell-forming organisms rely on carbon to make their shells, ocean acidification causes carbon to be in a shape that is inaccessible to these organisms.

“If carbon molecules are in the form of bicarbonate (HCO3-), which becomes much more abundant as more carbon dioxide is pumped into ocean water, these organisms cannot access the carbon as easily as when it is present as carbonate (CO32-), or will have to work much harder to get it,” Thomas says.

Expending extra energy to survive leaves less energy for what Thomas calls “the real thing of life:” reproduction. If reproduction is harder, populations of a large number of species will eventually begin to decline. Some of these vulnerable species like coral reefs and starfish are keystone species, which serve as the basis of an entire ecosystem. Without them, the entire ecosystem could collapse.

Davis points out that certain species are more affected than others. Examples of these highly vulnerable species include reef building corals, calcifying plankton, and shellfish like oysters and mussels.

“These are groups that not only build habitat for other species, like corals do, but can also form the basis of food chains that feed lots of larger animals, including humans,” Davis says. “These species can provide some important ecosystem services like filtering water and helping us maintain clean healthy coasts and estuaries.”

What are the impacts of ocean acidification to human society?

Around the world, human livelihood depends on ecosystems that are vulnerable to ocean acidification.

“Threats to things like coral reefs can impact everything from tourism dollars to food security and global biodiversity,” Davis says.

Thomas explains that some oyster farmers in the Pacific Northwest are already experiencing challenges in raising new oysters, as the pH of their seawater is too low. Ocean acidification will also negatively affect other species who aren’t directly impacted by the changes in pH.

“Many organisms that are vulnerable to ocean acidification appear somewhere low on the food chain, and ocean acidification can impact them, as prey for some of our favorite larger fishery species, things like salmon and tuna, as well as have direct impacts on shellfish fisheries, which we rely on directly,” Davis says.

While developed countries may miss out on some of their seafood favorites, Thomas points out that ocean acidification poses a unique threat to populations of less developed countries.

“What is concerning is that over a billion people around the world still obtain a significant portion of their daily protein from local fisheries that catch these vulnerable shellfish,” Thomas says. “Ocean acidification, therefore, has the potential to cause a major humanitarian crisis.”

What can be done by coastal decision makers to mitigate ocean acidification?

“Because ocean acidification is fundamentally a carbon dioxide problem, the number one thing we have to do is decrease the amount of CO2 that we are putting into the atmosphere,” Davis says. “That needs to happen at a structural, global level.”

Thomas agrees, and adds that coastal decision makers, including natural resource managers and local and federal agencies, would benefit from coming up with a new marketing strategy or catchphrase for ocean acidification that encapsulates the cause and urgency of the problem.

“There is so much of a focus on the term ‘global warming’ that it distracts us from other, non-land-based problems related to carbon emissions, like ocean acidification,” Thomas says. “As long as decision makers and the public fail to realize that this is a large-scale problem, they will not be excited to do anything about it.”

Davis adds that ocean acidification often works in concert with other environmental stressors such as overfishing as well as nutrient and material pollution, worsening the threats to ocean health and marine ecosystems.

“Coastal decision makers must make efforts to manage these environmental stressors and mitigate some of the compounding consequences,” Davis says. “For example, they might start by establishing policies that curb overfishing, or by protecting and restoring important habitats like mangroves and seagrasses.”

What can individuals do to help reduce ocean acidification and protect ocean health?

For Thomas, meaningful action starts with awareness.

“The first thing for individuals to do is to understand that humans do not just affect the atmosphere,” Thomas says. “Human activity has an immense impact on ocean health, including ocean acidification, plastic and oil pollution, overfishing, and more. The more we understand our impact on these complex systems and how it will affect our livelihoods, the faster we can begin to find solutions.”

After you have a basic understanding of the issues at play, taking action can take several different forms.

“The ultimate key has to be reducing our carbon footprint,” Davis says. “Wherever possible, individuals should make more sustainable carbon conscious lifestyle choices, as well as work to lobby governing bodies, coastal decision makers, corporations, and institutions to take ambitious climate action on our behalf.”

Learn more about Yale’s efforts to reduce carbon emissions on campus.