May 24, 2021

Sustainable healthcare and industry experts Dr. Jodi Sherman and Dr. Todd Cort introduce us to the green future of healthcare.

The global healthcare sector, which includes hospitals, medical facilities, and medical supply chains accounts for nearly 5% of global emissions. Climate change will pose new threats to public health, giving healthcare a responsibility to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions. Net-zero healthcare is a concept meant to fight the climate crisis while improving public health.

What does the term ‘net-zero’ mean?

“Net zero refers to the idea that we minimize all of the greenhouse gas emissions resulting from our organization’s activities to essentially zero when accounting for sources and sinks that we influence” Dr. Todd Cort, Faculty Co-Director for the Yale Center for Business and the Environment (CBEY) and the Yale Initiative on Sustainable Finance (YISF), says. “It is the idea of netting out the positives and the negatives in our emissions so you walk away with, essentially, no impact.”

Cort distinguishes carbon neutrality from a net zero approach (others define carbon neutrality differently).

“Mathematically, net zero and carbon neutrality are the same, but net zero has an implied intention to maximize the reduction of emissions before looking at purchasing offsets to eliminate the impact,” Cort says. “Whereas when it comes to carbon neutrality, some (but not all) emitters choose to emit as much as they want as long as they purchase more and more offsets to balance it out. This is not the philosophy of net zero healthcare.”

Cort adds that ‘net zero’ also looks at and addresses past emissions performance, where not all actors striving for carbon neutrality do so.

“With a net zero approach, we are not only trying to undo the emissions that we emit today, but we are also going to look at emissions that we have emitted over all of history and net those out as well,” Cort says.

What are the most carbon intensive aspects of healthcare currently?

Like any building, hospitals and other medical settings incur emissions due to the energy consumption of their facilities. However, the most carbon intensive aspects of healthcare are not happening at the hospital itself. Our experts point out that the bulk of healthcare emissions are happening elsewhere due to the actions and consumption patterns of the hospital. In fact, Sherman points out that about 70% of healthcare emissions come from the hospital’s supply chain.

“The vast majority of our emissions are not coming from the hospital’s rooftop, but especially by purchasing these manufactured goods and supplies and also disposing of them, we’re inducing emissions elsewhere.”

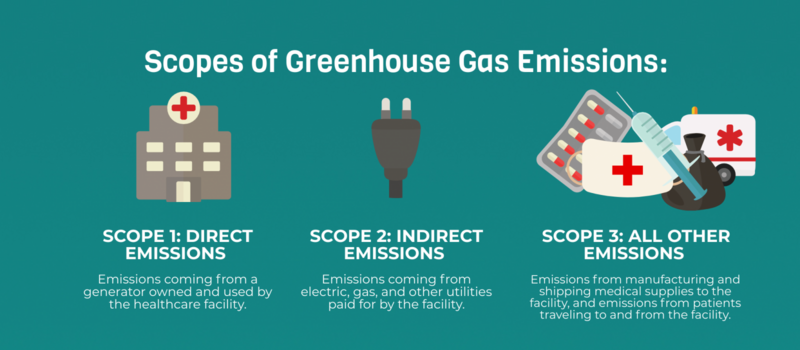

When measuring emissions reductions, “scope 1” refers to emissions an organization produces directly (for example, through a power plant or its fleet of vehicles), and “scope 2” refers to emissions from purchased electricity. All other emissions, including purchased goods and services, are referred to as scope 3 emissions. To understand scope 3 emissions, Cort encourages everyone to think about the lifetime of a single item in a hospital setting, like a plastic tube.

“It took energy for our supply chain to make that plastic tube, and then to sterilize it, package it, ship it to our facility, and then for us to throw that tube away and have it degrade,” Cort says. “These are all scope 3 emissions.”

Scope 3 emissions also include some aspects of patient care.

“Patients had to drive to the hospital to get care, they took prescriptions home, and all of that took energy that is included within the hospital’s scope 3 emissions,” Cort adds.

Why has healthcare lagged behind in cutting their emissions?

Despite the massive carbon footprint of the healthcare industry, the sustainability reporting and emissions drawdown in healthcare are not mandated nor entirely mainstream yet. It is important to note that healthcare systems have been working at above capacity during the COVID-19 pandemic, and much of their attention and resources have been dedicated to restoring public health and safety to our communities during this unprecedented time. However, as we recover from the pandemic, healthcare systems must continue considering their environmental impact.

“My assumption is that the lag in action has to do with the fact that healthcare already has a social mission. It is already doing good in the world by helping patients and treating disease,” Sherman says. “Unlike companies producing luxury goods that need to prove that they are good corporate citizens to be competitive, patients are not going to choose their hospital based on environmental performance. They’re going to choose it based on their healthcare needs and the outcome performance of their clinicians.”

Cort adds that the primary social mission of healthcare has diverted the attention away from their unsustainable practices. One outcome of this is that healthcare facilities currently do not need to monitor and report on their emissions or consumption the way that corporations and other institutions are often pressed to do.

“There is no price on carbon or plastics coming from healthcare that would drive change,” Cort says. “Unlike a corporation, there are no investors or any key levers of action that would drive the measurement and disclosure of this data … these practices are mostly under the radar right now.”

Further, patients and other stakeholders in healthcare still have fear and hold some misconceptions around what sustainability in healthcare would actually mean.

“I think there is a false perception that there are tradeoffs with sustainable energy consumption and quality of care, yet there are many things that can be done more efficiently without compromising quality of care at all,” Cort says.

What are the benefits of reducing healthcare emissions?

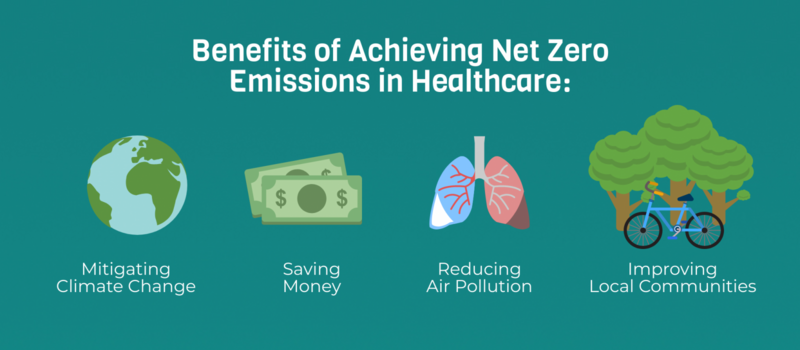

A reduction of emissions would help mitigate the worst impacts of climate change in years to come, especially reductions happening at the massive scale of healthcare systems worldwide. But even beyond the long-term environmental benefits, there are numerous other positive effects of achieving net-zero healthcare.

“When we switch to renewable energy and become more efficient to reduce our emissions, we are also cutting air pollution, which is the number one cause of noncommunicable disease and death globally right now,” Sherman says.

Cort agrees and adds that when healthcare systems eventually move toward offsetting any residual emissions they have, they can choose offset projects that benefit the local environment and therefore the health of local patients.

“There is this possibility of a tertiary link where healthcare organizations and insurance companies can invest in green spaces or active transportation like bikes that not only reduce their carbon emissions through offsets, but also improve healthy lifestyles by giving people access to the outdoors and nature.”

Importantly, Sherman adds that improving efficiency in facility operations and in supply chains will also save money for healthcare systems.

How do we get to net-zero healthcare? What is currently being done about it?

The “low hanging fruits” for emissions reductions, Sherman explains, can begin with medical facilities and operations themselves. These facilities will need to become more energy efficient and will need to source their energy from renewable sources.

However, addressing the magnitude of the problem – particularly the scope 3 emissions – will go beyond the hospital walls. Cort explains that achieving net-zero healthcare will require a coordinated effort between medical facilities, medical supply chains, insurance companies, government leaders and policymakers, and the public. He refers to these stakeholders as “drivers”.

“I think about this as a series of cogwheels,” Cort says. “You can have one cogwheel, which is the driver, that sends the entire chain of wheels going … There are numerous drivers for the healthcare sector, and while one driver is okay, four or five different drivers getting the engine going is even better.”

For example, when it comes to changing the supply chain, Sherman says that medical facilities should use their purchasing power to target some of the ‘hot spots’ in scope 3 emissions, which include pharmaceuticals, chemicals, medical devices and supplies, and food.

“We can try to create competition in the marketplace by only contracting with companies that are reporting their emissions and using science-based targets to draw down those emissions,” Sherman says.

Cort adds that alternatively, medical facilities can begin by identifying their largest suppliers and influencing them to change their practices and to ‘engineer out’ some of the inefficiencies and emissions in their processes.

“In order to do any of this, however, it starts with measurement,” Sherman says. “You cannot strategize how to get there unless you measure where you are at, and that’s what we are doing poorly in the United States.”

Sherman adds that even the institutions who are voluntarily measuring and reporting their emissions are leaving out those scope 3 emissions, which are the largest source of healthcare emissions. Incentivizing or even mandating the measurement and reporting of healthcare emissions is something that Sherman believes would drive change.

“In healthcare, we already financially incentivize improvements to the quality of care, so I see an opportunity to financially incentivize sustainability,” Sherman says. “For example, one way to incentivize it might be to say, if you want to get paid through government health insurance such as Medicare and Medicaid and the Veterans Affairs health systems, you must be reporting your emissions and have a plan to track and reduce those emissions according to international timelines.”

Are there things that individuals can do to support this endeavor?

Our experts agree that it depends on the individual.

Sherman points out that if you are a clinician, you can begin to be more conscious about your clinical resource consumption habits and the materials that you are prescribing. These small changes will begin to create a bottom-up culture of sustainability within healthcare settings.

Other healthcare employees and patients can also contribute in their own scaled ways.

“Some individuals have the authority and the power to create bigger changes within an organization, like to embed energy efficiency into their systems and sustainability into their purchasing standards, and if you have that power, you should use it,” Cort says. “Other individuals have less influence to make big changes, but they don’t have to take a back seat. Whoever you are, just focus on doing what you can do at work or at home, like turning off the lights.”

What is Yale Doing?

The Yale Program on Healthcare Environmental Sustainability (Y-PHES) and the Yale Center for Business and the Environment are co-hosting a 3-part symposium, Care Without Carbon: The Road to Sustainability in U.S. Healthcare, May 27th, June 3rd, and June 10th. Registration is free.

Yale-New Haven Health System is developing and implementing a Center for Sustainable Healthcare, collaboratively with Y-PHES, so it can work towards net zero emissions and be better stewards of the environment. Lots of opportunities exist to work collaboratively across the Yale community, as part of the Yale Planetary Solutions Project.